Dedicated to Biljana Vasilevska-Trajkoska (†2024)

At the close of the past year, 2024, the 30th anniversary of Before the Rain, the opus magnum of Milcho Manchevski, was commemorated with due attention and honor. This cinematic masterpiece gifted the world a profoundly moving and prophetic testimony of time, space, and the interwoven currents of human life. Its visual poetics, rich in symbolism and philosophical depth, were accompanied and ennobled by the music of the now-legendary Macedonian group Anastasia—a musical expression that transcends the linearity of sound in a metaphysical way, transforming into a prayerful, contemplative, and mystical invocation.

From that majestic soundscape crafted by Anastasia, one composition remains immortally powerful, timelessly beautiful, and indelibly etched in the collective memory of my generation, as well as those before and after me. It is the most fragrant blossom of that musical anthology: Passover (Premin). If Anastasia represents the resurrection in the Macedonian musical world, then Passover is Pascha itself in the beyond.

Passover, composed and written by Goran Trajkoski, is one of the epochal musical moments in Macedonian history. It is a creation that transcends all temporal and spatial boundaries—a song that does not belong solely to Macedonia but to every human being searching for spiritual freedom.

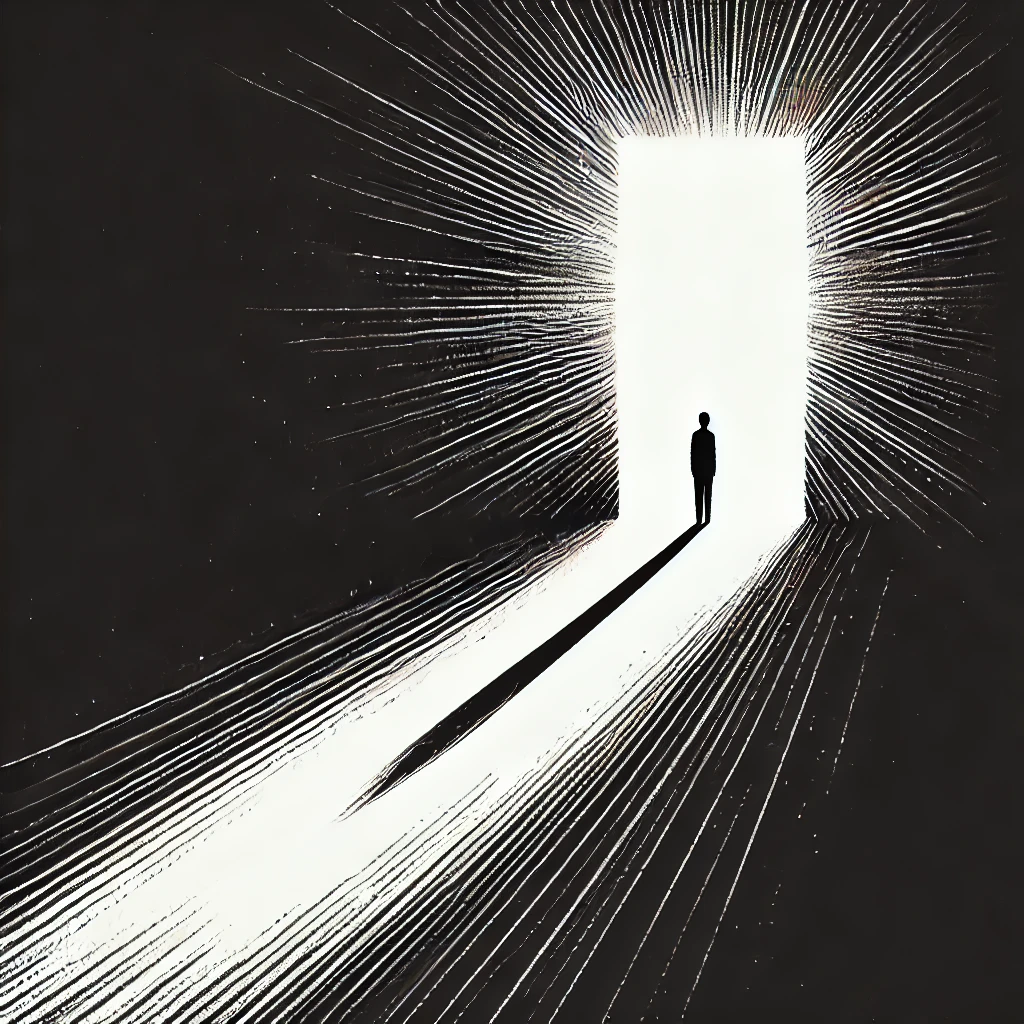

In Orthodox revelation, the passover (passage) is never merely a physical act; it is an ontological transformation. It is an encounter with one’s inner being, with one’s sins, fears, and hopes, with the light and darkness that ceaselessly wage war within us. Passover is precisely that—a lyrical yet liturgical evocation of the deepest struggle in human nature: to abandon the transient, to find a bridge, a gateway to true existence.

It is not merely a musical piece but a hymn of our time—a hymn of the human soul, of its affliction, its doubt, its struggle, its thirst for life, for passage from the temporary to the eternal, from this world of malice to that of boundless goodness. With the primordial sounds of Eastern Orthodox music, of Byzantine chanting, and of a minimalist monotony that ascends into a cosmic lament, Passover by Gotra is not just a well-structured composition. It is that, but it is also far more. It is a prayer, a cry, repentance, love for the Homeland—both earthly and heavenly—a passage toward that which is immeasurable yet profoundly real.

The song begins with the resonances of something that feels like a deep inner quest—something essential and primordial. It gradually unfolds into a sound reminiscent of an echo from ancient times, as if it is not merely heard with the ears but, above all, with the heart. The voice, at first a philosophical reverberation posing essential rhetorical questions, rises in exaltation, calling for an exodus from the world of vanity and an entry into the realms of the Divine. Is this the fundamental cry of our inner being? Is it the summons of the final hour, the sound of the human soul at last confronting its eschatological destiny?

The lyrics, simple yet immeasurably profound and penetrating, offer a kind of doxological, prayerful testimony:

And He, from whom I am,

Will not allow it.

He Who has loved me,

Will not abandon me,

Alone, amidst a dense forest,

Of hands that grasp at me.

There is something in these verses that powerfully resembles biblical hymnography—a proclamation that God’s mercy will never forsake us. A realization matures within the human soul: that divine love has the final word, that it is not easily escaped, and that wherever we may be, it will find us.

We grew up with this song. At least I did—literally. I say literally because in one of my conversations with Gotra, I asked him to share more about the genesis of Passover: the first demo version was recorded in a different era—not so distant, yet vastly different—on a cassette recorder, during a time when God and the Church were taboo subjects. He played it on an acoustic guitar in the summer of 1986, in the generation of Chernobyl, to which the author of these lines also belongs.

And so, you can understand what a profound honor it was for me, together with my friends from our high school rock band Syd, to have the blessed opportunity to be the opening act for Gotra’s Mizar in Bitola, a little over two decades ago.

Thus, we did not just grow up listening to Passover; we grew up with it—as beings who, perhaps unconsciously, carried within themselves the secret of an era, the imprint of an unceasing search, a call toward something we could not always explain but deeply felt. Several generations of souls from our land have been raised on its sounds and lyrics, and even the newer generations, regardless of their personal beliefs and understandings, cannot remain indifferent to its spiritual grandeur.

Some experience it as a mantra, as a ritual hymn of a mysterious faith; others hear in it a call to repentance, to a transformation of mind, to a different way of life. For many, it serves as a reminder of our transience—that the time we live in is not our own, that man is but a traveler in this world, a fugitive from his own shadow, whose true homeland is not of this world.

In this age, when the world is overburdened with noise, Passover remains a solemn, exalted, serene—yet profoundly stirring and sobering—call:

I stand,

Lest I be found unworthy

Before I know not whose,

Whose door.

And I check again—

Am I awake or dreaming?

Do I contemplate or delude myself…?

This Song of Songs in contemporary Macedonian music is the personal emblem of its creator, Goran Trajkoski—a genius composer whose music is not merely a harmony of sounds but a journey; not just a melody but a passage into another, deeper reality. His work, rooted in the mysticism of Orthodox spirituality, in the spirit of the Romiosini, yet also in the experimental rock avant-garde of the global music scene, remains an indelible mark upon Macedonian culture—a code not easily deciphered, yet one that anyone who has heard it feels deeply within the heart. His art is neither mere rock music nor simply a neo-folk interpretation of the past. He has forged his own musical language, interweaving the ancient chants of Eastern Orthodox hymnography, the harmonies of Macedonian folk traditions, and the textures of modern electronic and ambient music.

Passover by Gotra is a confession, a revelation—a voice emerging from the depths of an awakened soul as well as from the inaccessible heights of eternity. And so, with deep conviction, we can say that Goran Trajkoski is not merely a musician—he is, above all, a contemplative. Like a kind of musical hesychast, he seeks and offers, through his compositions, answers to the greatest questions of human existence.

There is something unusual, something sacred in Goran Trajkoski’s music. Something that compels the listener to fall silent, to pause, to listen attentively and with an inexplicable reverence—like when one opens the Holy Scriptures and turns the pages that speak of the mystery of being, of the meaning of man. This is not easy music. It is not for mass consumption. It does not belong to our time, and yet it is desperately needed for our time. It is music for reflection, for contemplation, for journeying, for awakening.

Among other works, Goran Trajkoski is also the composer of the score for Ilija Iko Karov’s documentary film on the Bigorski Monastery, “1000 Years – Witness of the Light”, for which he received the award for Best Music at the international film festival “History”, held last year in the city of Aspern, Austria.

Undoubtedly, Gotra has created something universal, something that transcends language, something that breaks the chains of time and space and never ceases to captivate those who approach it with an open spirit. With every resounding of his “heavy voice” in his “new hymns”, that mystical connection between man, his existence, and the infinite is renewed. And as our Elder, Bishop Parthenius, concludes: “Gotra belongs among the greatest gifts bestowed upon Macedonian musical, cultural, and spiritual life in our recent history.”

Like prophetic voices,

Like patristic hymns,

Let me cry out from the depths,

Let me sing in the wilderness,

Like a stone through the mountains,

Let me tumble into the abyss,

Like a rushing mountain stream,

Let me hasten unto Thee,

Let me run toward Thee,

To offer Thee glory.