August 1995, on the eighth day of the month, the commemoration of Saint Paraskeva of Rome. The sun, majestically rising between the mountains of Bistra and Krchin, reigns sovereignly over the entire region of Reka, revealing in full the primordial beauty of the Radika Gorge. At that time, I was still acquainting myself with the God-given beauty of Reka, and from its nature, as if reading from a fifth Gospel written directly by God’s hand, I was discovering the transcendental magnificence of the supreme Creator and Artist. A few days had passed since my monastic tonsure, and carrying within me the quiet grace of monasticism, each day of my life became a revelation. Through prayer and liturgical services, I communed spiritually with the old monks of Bigorski, my predecessors, and I uncovered the wondrous history of the Monastery and this region. I learned about the spiritual giants originating from Mijachia, and about the glorious events hidden under the veil of history. Although the Monastery had faded under the pressure of time and neglect during the previous societal regime, lacking even basic living conditions, it preserved the spirit of the past – it represented a sacred mystery. Even though the history of Mijachia and Bigorski was not foreign to me, as my ancestors were of Mijachian descent and I had heard and read quite a lot about their story, when I arrived at the Monastery, everything felt new to me, revealing itself like a mystery.

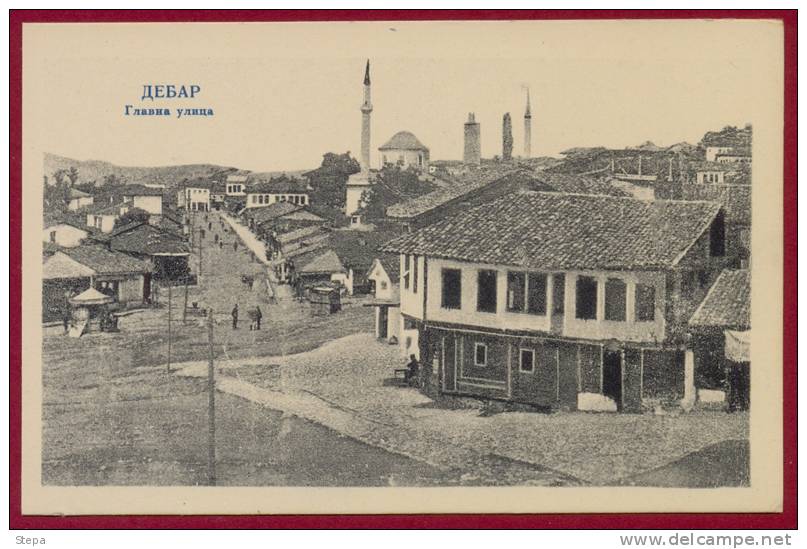

Together with my brother in Christ, the current Metropolitan of Bregalnica, Bishop Ilarion, and my mother Zhivka, who was staying at the Monastery at the time to help us, we were supposed to travel to Ohrid. On the following day, the feast of Saint Clement of Ohrid, my ordination into the rank of hieromonk was scheduled to take place in the Church of the Most Holy Theotokos Perivlepta. Since we had no vehicle at the time, we asked some visitors to the Monastery to take us to the city of Debar. While waiting at the bus station for the “Proleter” bus, which ran the Skopje-Debar-Struga-Ohrid route, an elderly man approached us. He was neatly dressed in a white shirt, a dark sleeveless vest, brown woolen trousers, polished shoes, with a well-groomed face, and a hat on his head. It was evident that he was a man of urban culture and bearing, an old Debar resident, dressed in the traditional way of the old Debar townsfolk, regardless of their ethnicity or faith. He addressed us very politely and respectfully, removing his hat and bowing slightly toward us:

-

“Good day, young gentlemen. My deepest respect to you. I heard that some young people had arrived at the Monastery, and seeing how you are dressed, I assume it is you. I am very glad that the Monastery will come to life again, it is part of our region, and we all love and respect it. As priests, I want to tell you that we, the Albanians from Debar, have great respect for you priests because, you should know, this city was once saved by a priest. Our elders have told us that once, the city was on the verge of being razed to the ground, burned, and all the Albanians in it were to be killed, but at that moment, the priest of the city stood up and prevented the bombing. That’s why to this day we hold great respect for you, the clergy.”

The appearance of this man and his story left a deep and pleasant impression on me. I felt the culture of coexistence and mutual respect, characteristic of this region. Soon after, I realized that in Debar and the surrounding area, the spirit of solidarity and coexistence was indeed alive. There were moments when we encountered greater respect for the monastic habit in Debar from local Albanian Muslims than from some so-called “Orthodox” in Skopje.

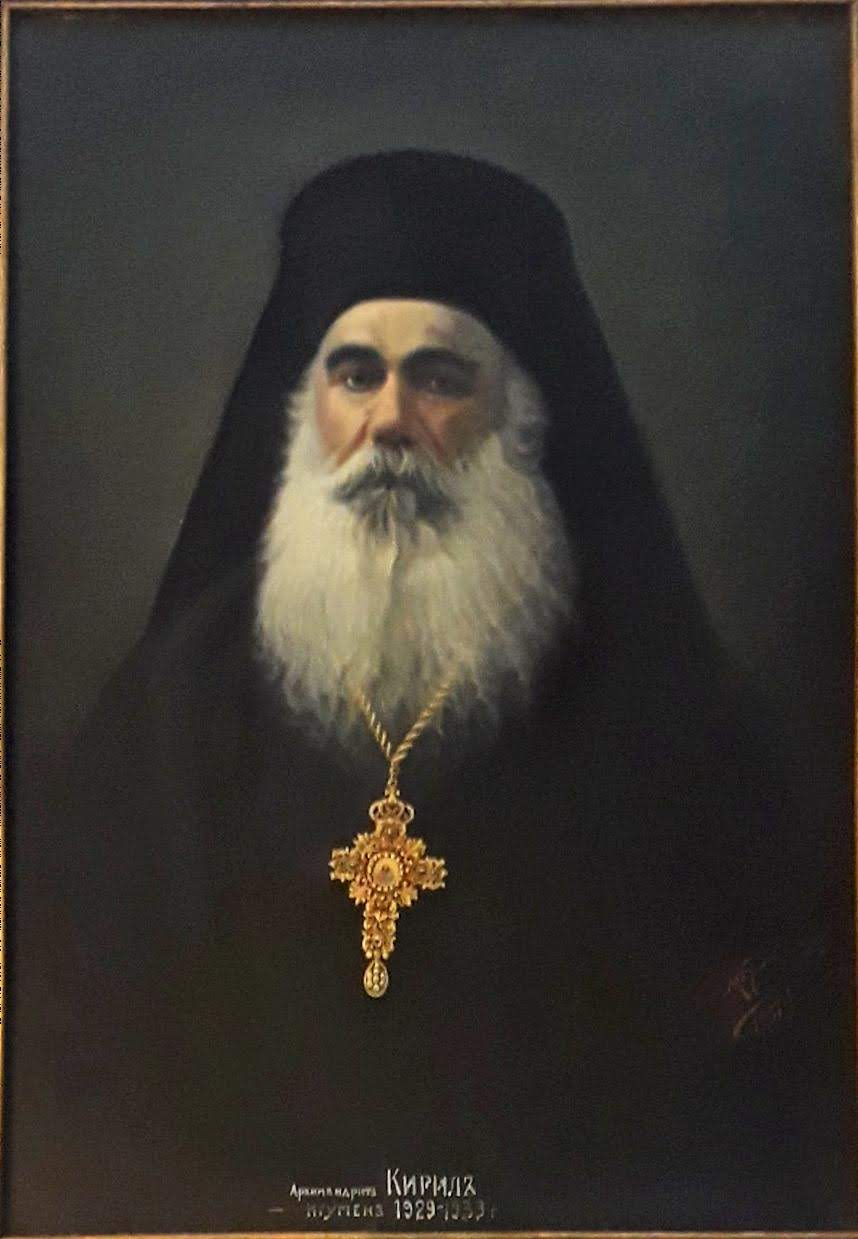

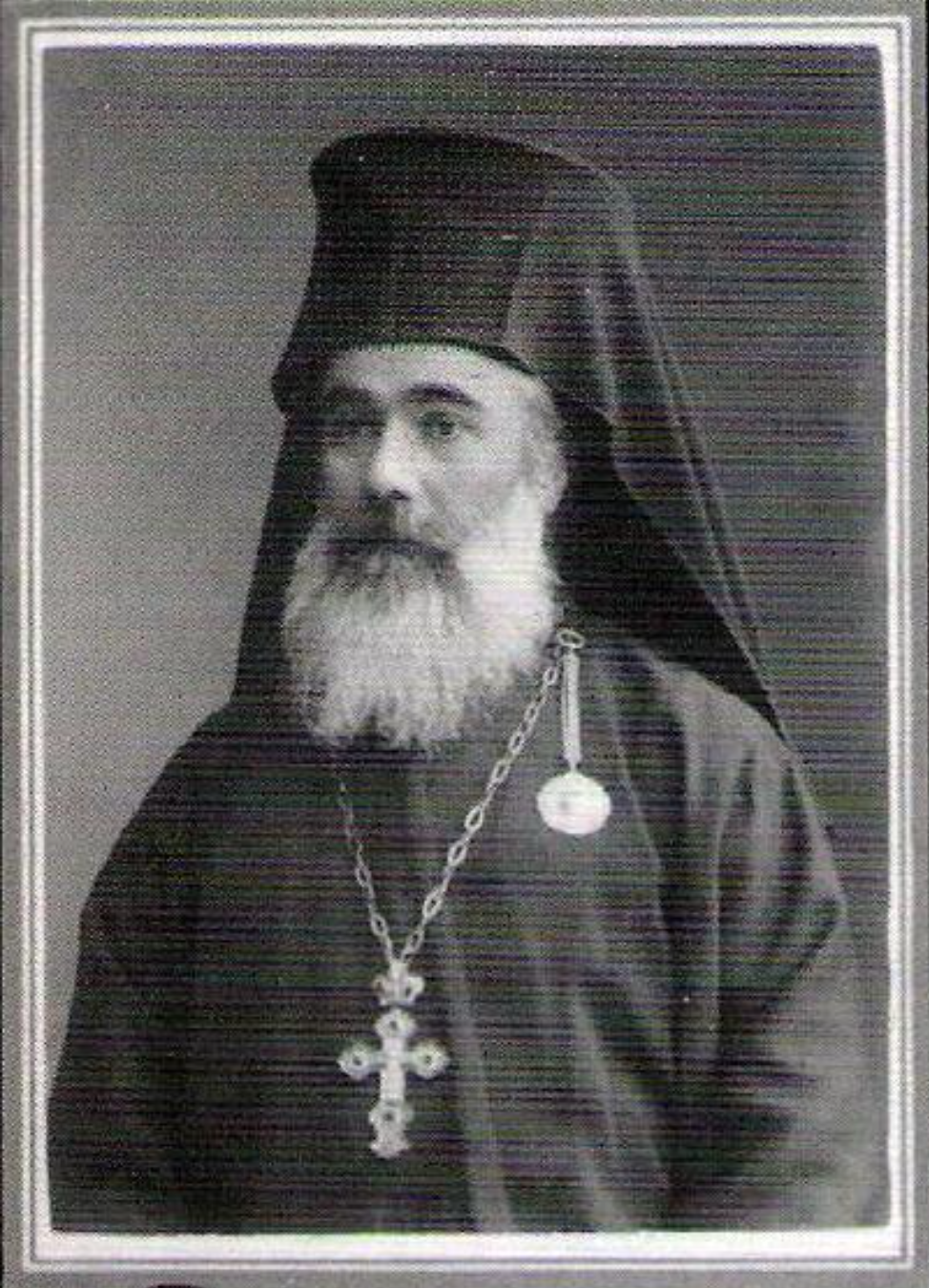

Later, I researched more about the tradition that the old Debar native had shared with us, and I discovered that it referred to an event that took place in October 1918. During the retreat of the Bulgarian army from Ohrid, their 19th regiment was attacked by an armed group of Albanian mercenaries near the city of Debar. At that time, the commander of the regiment ordered the entire artillery to be positioned around the city and for the lower part of the city, where the Albanian population lived, to be razed to the ground. However, when the lieutenant colonel heard the ringing of the church bells, he inquired why they were ringing. He was told that the Archimandrite Kyril, the archiepiscopal vicar in the area, had blessed it. The commander then ordered Archimandrite Kyril to be summoned to him. When Father Kyril met with the commander, he persuaded him to abandon the plan to destroy the lower part of the city, as the common people were not to blame for the attack that had occurred. Thus, this servant of Christ, embodying the universal love of Christ, saved the Albanian population from complete destruction.

Archimandrite Kyril himself writes about this event in his Short Memories from My Past Life (1861-1931), published in Sofia in 1931—a book we discovered a few years ago:

“The next morning, early at dawn, the 19th regiment, retreating from Ohrid and heading toward Old Bulgaria, passed through Debar. The soldiers of the 19th regiment had encountered the soldiers from a partisan unit, composed of Albanian-Turks (that is, Albanian Muslims—at that time, ‘Turk’ was synonymous with ‘Muslim,’ regardless of ethnicity) who did not speak Bulgarian. The soldiers of the 19th regiment demanded that they surrender their weapons, but those from the partisan unit, who were also Bulgarian soldiers serving for pay, refused to hand over their weapons. Since they could not understand each other, a fight broke out, resulting in many casualties on both sides… The lieutenant colonel of the 19th regiment, upon hearing the ringing of the bells in the upper Christian quarter of Debar…, immediately sent two soldiers to summon me to the lower part of the city, where the Bulgarian soldiers were stationed, and I went there at once. When I arrived, I found the entire Turkish (i.e., Muslim) population out of their homes, gathered outside the city with drums, while the artillery had positioned itself on the heights above Debar, waiting for the command to begin bombing and burning the city. As soon as I descended to the lower part of the city, the lieutenant colonel received me courteously and asked about the gunfire he had heard from the local population. I assured the lieutenant colonel that there was no rebellion in the city of Debar, and asked what fault the peaceful local Albanian population had, to deserve such a harsh punishment without any guilt. I said, ‘I assure you, Mr. Lieutenant Colonel, trust my words, there is no uprising in Debar, and no threat to anyone.’ The lieutenant colonel listened attentively to my words and changed the order to burn Debar, giving the command for the gathered Turkish (i.e., Muslim) population to return to their homes.”

Since then, the story of the “priest who saved the Albanians and other Muslims in the city of Debar” has been etched in the collective memory of the people of Debar.

I am sharing this story because I have become deeply connected with this region, where I have lived continuously for nearly three decades, feeling it as my own, and I have witnessed the culture of coexistence in Debar and the surrounding area, which has survived to this day. I pray that this cultural achievement endures forever. The tradition of the priest and the salvation of Debar is still recounted today, even though more than a century has passed since the event. The native Debar residents have shown that they know how to remember good deeds and be grateful and noble. This gives these people an aristocratic spirit and cosmopolitan breadth.

Written by Bishop Parthenius, Abbot of the Holy Bigorski Monastery

Below is a brief biography of Archimandrite Kiril of Rila, another great spiritual figure from the Mijak region of Macedonia.

Archimandrite Kiril of Rila was born in 1861 under the secular name Kiprian Stefanovski in the western Macedonian Mijak village of Bituše in the Reka region. This is why he signs his writings as “Mijak.” His first monastic steps were taken at the Bigorski Monastery of the Honorable Forerunner and Baptist John. He became a novice at the Rila Monastery on September 14, 1878, and was tonsured on November 29, 1880, receiving the name Kiril. He was ordained a hierodeacon on May 28, 1884, at the Rila Monastery, and on January 7, 1890, he was ordained as a hieromonk. In 1895, he completed his studies at the Kiev Theological Academy.

After returning from Kiev in 1895, he taught at the Samokov Theological Seminary. In the following year, 1896, he departed for the Ottoman Empire to support church and educational efforts. He first became the president of the church community in Xanthi. In 1898-1899, he taught at the Constantinople Theological Seminary. From 1900 to 1908, he served as the president of the church community in Gevgelija. In 1909, he was appointed administrator of the Adrianople Diocese. In May 1911, he was transferred to administer the Drama Diocese. In August 1913, following the Second Balkan War, he left Drama, and in 1914, he became protosingel (senior monk) in Vidin under Metropolitan Kiril of Vidin.

After the liberation of Debar in 1915 and the death of Metropolitan Kozma of Debar in January 1916, the people of Debar appealed to the Holy Synod of the Bulgarian Exarchate, requesting that Archimandrite Kiril be appointed administrator of the Debar Diocese, as he was a native of the region. The Synod recommended to Metropolitan Boris of Ohrid, who at the time also managed the Debar Diocese, to appoint Kiril as his protosingel in Debar. Archimandrite Kiril of Rila arrived in Debar on April 26, 1916. He managed the diocese until December 18, 1918, when, following the end of the war and the withdrawal of Bulgarian troops, he was forced by the Serbian army to hand over the administration to Serbian church authorities.

In 1922, he was a candidate for the position of Metropolitan of Sofia but came in second with 26 votes. In 1924, he returned to the Rila Monastery as a confessor. He served as abbot of the monastery from January 1, 1929, to September 1, 1933. During his tenure as abbot, the monastery was equipped with a water supply system, sewerage, and electricity. He built a new building for the metochion in Rila. He also established the “Rila Monastery” fund.

In 1931, along with Bishop Ilarion of Nišava, Hieromonk Jeronim Stamov, Father Hristo Butsev, and Protopriest Trifon Stoyanov, he was part of the delegation of Macedonian clergy that visited several European capitals and sent a petition to the League of Nations in Geneva.

He passed away on October 22, 1946. He was buried in the monastery cemetery of St. John of Rila. Descendants of his family still live in Gostivar to this day.

May his memory be eternal!