Jean-Jacques Rousseau, one of the most eminent French philosophers, Enlightenment thinkers, and writers of his turbulent and transformative century, was born on June 28, 1712, in the beautiful Swiss city of Geneva. He completed his earthly journey on July 2, 1778, in Ermenonville. Later, his remains were posthumously transferred and interred in the Hall of French Heroes at the renowned Panthéon in Paris.

Rousseau was an original philosopher across various philosophical domains. His contemporaries called him the “Apostle of Nature,” due to his profound love for nature and for a natural way of life.

His first significant recognition came with his work, Discourse on the Sciences and Arts (1750), which he wrote in response to the Dijon Academy’s question: “Has the restoration of the sciences and arts contributed to the purification of morals?” The fundamental ideas he developed in this discourse continued to resonate through his later writings.

One author, speaking of Rousseau and his core philosophy, wrote: “Man is by nature free and good, but selfishness, as well as unjust, irrational, and corrupt systems of governance, have suppressed and stifled what is natural in both individual and social life.“

Rousseau complemented his conviction in the impermanence of human institutions with a belief that institutions endure longer when grounded in the principles of reason, that is, in human nature itself, founded on a social contract that binds both the rulers and the ruled equally.

This is undoubtedly true.

Rousseau left behind other notable works: The Social Contract (1762), Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (1754), Confessions (an autobiography), and more. He also wrote several musical studies, including Musical Dictionary, Dissertation on Modern Music, and others.

He exerted a tremendous influence on French ideology, impacting numerous French and German authors, especially writers and philosophers such as Kant, Fichte, Hegel, Schiller, Goethe, Byron, Radishchev, and Leo Tolstoy.

Marxist philosophers like Yudin, Marchevsky, and Rosenthal acknowledged that Rousseau was a man of deep faith in God and held a profound conviction that God is the source of all existence. In his educational novel Emile, Rousseau developed his ideas on upbringing. According to Dr. Radivoj A. Josić, in this same work (1762), Rousseau wrote a beautiful, prose hymn about Christ:

“I confess to you, my son, that the grandeur of the Holy Scriptures overwhelms me, and the sanctity of the Gospel speaks directly to my heart. Look at the books of the philosophers with their pompous language: how insignificant they appear beside the Holy Scriptures! Should we consider the gospel story a mere invention? My friend, such a thing cannot be invented! The works of Socrates, in which no one doubts, are less substantiated than the works of Jesus Christ.”

On certain passages in the New Testament, Rousseau reflects: “And so, what is one to do, faced with all these contradictions? My son, one must always be humble and careful! One must respect in silence what cannot be dismissed or understood, so that the only thing left to man is to bow before the Great Being who alone knows the truth.”

Rousseau devoted his deepest reflection and admiration to the character of Christ:

“But is it possible that the One spoken of in the Gospel is merely a man? Could His life and teaching be the dreams of an ambitious party leader? What gentleness! What purity in His morals! What a moving appeal in His teachings! What grandeur in His principles! What profound wisdom in His replies! What self-mastery in His difficult trials! Where is the man, where is the sage who could act, suffer, and die as He did, without weakness and without boasting? … Oh, how blind is the one who dares to compare Socrates, the son of Sophroniscus, with the son of Mary – Jesus Christ. What a vast distance between the two of them!”

In conclusion, Rousseau contrasts the death of Christ with that of Socrates:

“The death of Socrates, which took place while he was calmly philosophizing with his friends, is the gentlest death: one that a man could only wish for. In contrast, the death of Jesus, insulted and cursed by an entire nation, passing in agony, is the most terrifying death, one that fills us with dread. Socrates drank the cup of poison and blessed the jailer who gave it to him, weeping. In the midst of His own excruciating pain, Jesus prayed to God for His merciless enemies. Truly! If the life and death of Socrates are those of a sage, then the life and death of Jesus reveal God Himself!”

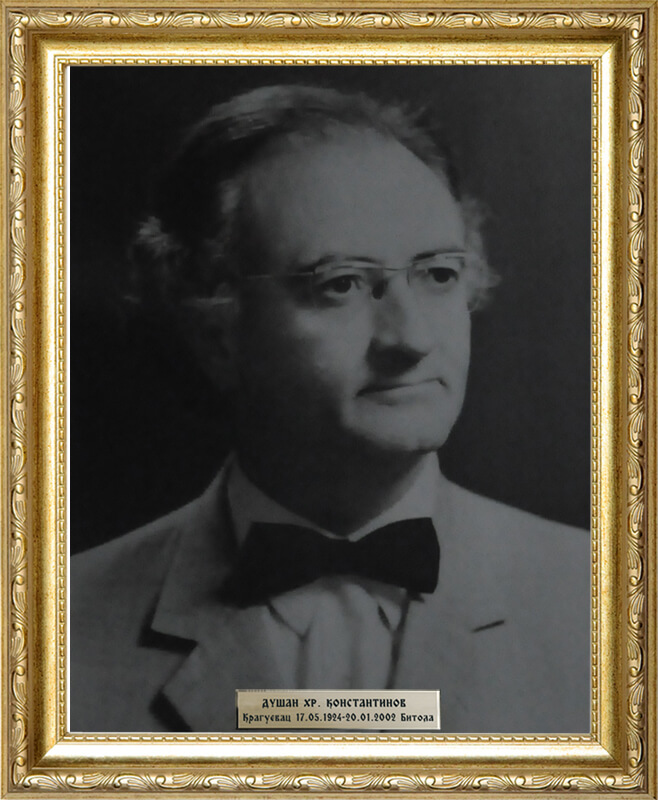

Dušan H. Konstantinov (b. 1924 – d. 2002)

Dušan H. Konstantinov was a Macedonian intellectual and researcher, celebrated for his pioneering work in creating the first complete translation of the Holy Scriptures into modern Macedonian, thereby paving new paths for the nation’s spiritual and linguistic growth. Known for amassing one of the largest private libraries in Macedonia, he partially donated this collection to the Bigorski Monastery, offering broad access to knowledge and spiritual resources. Holding two doctorates from the Yugoslav era, Konstantinov is counted among Macedonia’s most influential cultural figures, leaving a lasting impact on the country’s scientific, spiritual, and cultural landscape.