“The luminous figure of the Nazarene has left an indelible impression on me…”

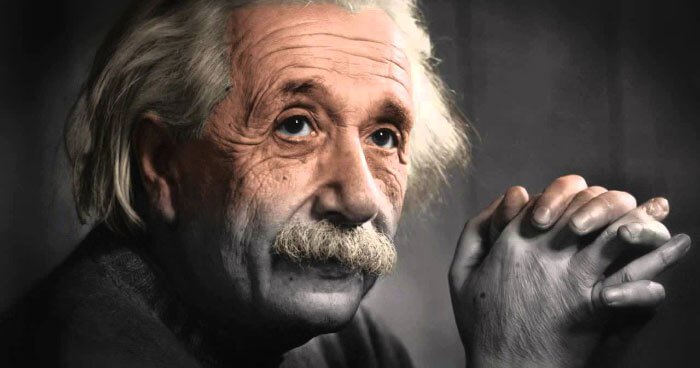

Albert Einstein, one of the greatest scientific geniuses of the twentieth century, was a globally renowned theoretical physicist hailed as “the foremost architect of the new era in physics.” He was born on March 14, 1879, in Ulm, Germany, into a Jewish family. His father, Hermann Einstein (1847–1902), was a merchant dealing in chemicals and electrical materials, operating initially in Germany and later in Switzerland and Italy. His mother, Pauline Einstein (née Koch, 1858–1920), was a diligent homemaker dedicated to her family.

In 1880, the Einstein family moved to Munich, where the young and gifted Albert began his formal education. At the age of fifteen, he relocated to Aarau, Switzerland, to continue his studies. There, he enrolled at the Zurich Polytechnic, studying mathematics and physics. Faced with the discrimination against Jews in Germany, he renounced his German citizenship and obtained Swiss nationality. His first academic papers were published when he was just 21 years old.

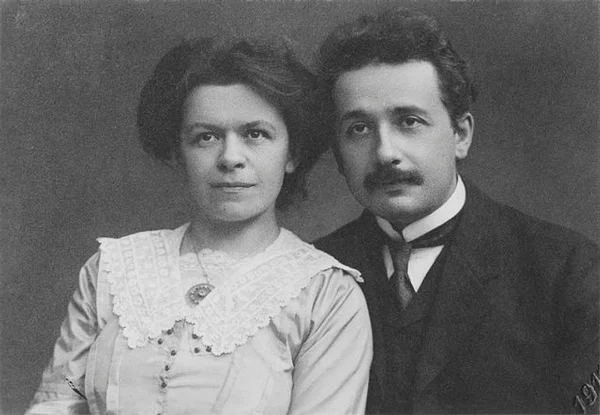

In Zurich, Einstein met Mileva Marić, a native of Novi Sad (some biographical accounts suggest she was from Titel). Mileva, who was a year older than Einstein, was also a student in Zurich. They fell in love and were married on January 6, 1903. A brilliant mathematician, Mileva played a pivotal role in assisting Einstein with his scientific work. It can be said that, in the early stages of his career, Einstein might not have achieved his success without her contributions. Nevertheless, their marriage was not a happy one and ultimately ended in divorce.

In 1905, Albert Einstein published two groundbreaking works: “The Theory of Relativity” and an explanation of the law of the photoelectric effect using quantum theory—a contribution for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921. That same year, he completed his doctorate with a dissertation titled “A New Determination of Molecular Dimensions.” By 1909, he had become an associate professor in Zurich, and in 1914, he was appointed director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in Berlin, where he also became a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. Reclaiming his German citizenship, he sought to contribute in some way to the Weimar Republic.

As a Jew and a staunch opponent of fascism, Einstein condemned the criminal mantra of “think like us or die.” In 1933, he fled to the United States and settled in Princeton, where he continued his scientific work until his death in 1955. Due to his unwavering stance against fascism and war, Einstein was regarded as one of humanity’s greatest progressive minds. In his honor, a chemical element discovered in 1954 was named Einsteinium.

Einstein was not only a scientist but also a man of profound faith. His understanding encompassed both Judaism and Christianity, and his reflections on Christ, our Savior, stand as precious gems of a sober, logical, and brilliant mind:

“The luminous figure of the Nazarene has left an indelible impression on me… If the Judaism of the prophets and the Christianity of Jesus, as He taught it, were stripped of the later accretions, the world would receive a doctrine capable of healing all the social ills of humanity… Jesus is vastly greater than the comprehension of those who are masters of expression. No one can destroy the sharpness of Christ’s insight… No one can read the Gospels without feeling the presence of Jesus. The pulse of His personality beats in every word… It is impossible not to recognize that Jesus lived and that His words are uniquely wonderful. Even if certain individuals before Him spoke something similar, no one expressed it as divinely as He did.”

Modern German author Johann Wickert believes that Einstein’s faith can essentially be described as “cosmic religiosity,” perhaps because he was perplexed by Einstein’s statement: “I believe in Spinoza’s God.”

However, Albert Einstein was neither a pantheist nor an atheist. He himself best explained his belief in a personal God:

“The usual assumption that I am an atheist is based on a profound misunderstanding. Whoever finds this in my theories has hardly understood them. Such misinterpretation shows disrespect toward me. I BELIEVE IN A PERSONAL GOD and can say with a clear conscience that I have never supported the atheistic worldview. As a young student, I broke away from the scientific perspectives of the 1880s and from those who supported the science of evolution. We must realize that development continues, not only in technology but also in science—particularly in the natural sciences. Today, many scientists are convinced that religion and science are not at odds with one another.”

Einstein also shared his personal convictions about the critical role of religion in human progress:

“As for me personally, I am convinced that without religion, humanity would still be at a barbaric stage of development. All social life would take place under unimaginably primitive conditions. There would barely be any security for life or property; and the struggle of each against all—which is an unrelenting human instinct, in my firm belief—would manifest in far more brutal ways than we see today. Religion has been the guiding force that has helped humanity progress in all areas.”

Einstein understood that God is Spirit, continually creating new beauty and sovereignly reigning over the universe. Within this framework, he shaped his own conception of God: “My faith consists in humble admiration of the supreme Spirit who reveals Himself in the smallest details that we can comprehend with our weak and limited minds. This deep, emotional conviction of the presence of a SUPERIOR REASONING POWER, which reveals itself in the incomprehensible universe, forms my concept of God.”

The brilliant Albert Einstein was not only sincere but also humbly modest before God.

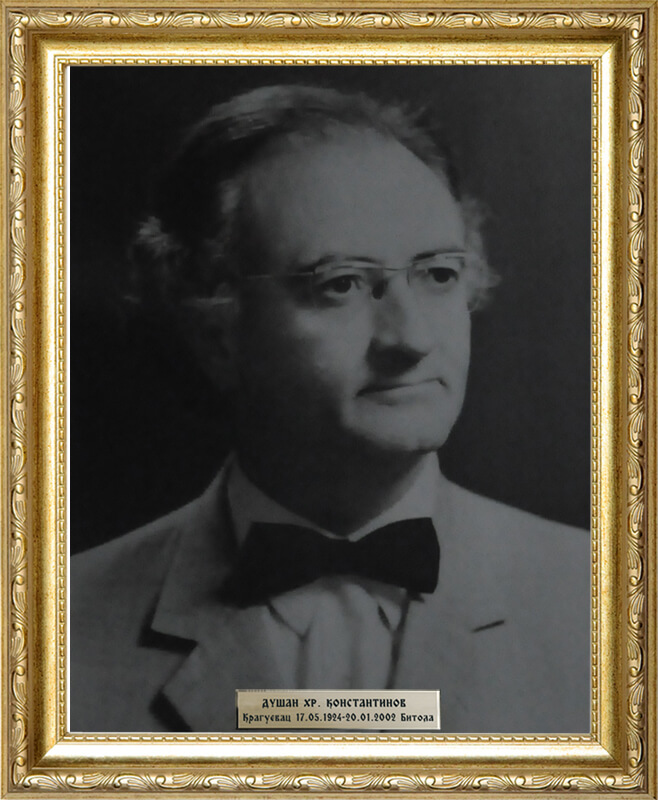

Excerpt from the unpublished book, “The Faith of Great Minds,” by Dr. Dušan Hristov Konstantinov

Dušan H. Konstantinov (b. 1924 – d. 2002)

Dušan H. Konstantinov was a Macedonian intellectual and researcher, celebrated for his pioneering work in creating the first complete translation of the Holy Scriptures into modern Macedonian, thereby paving new paths for the nation’s spiritual and linguistic growth. Known for amassing one of the largest private libraries in Macedonia, he partially donated this collection to the Bigorski Monastery, offering broad access to knowledge and spiritual resources. Holding two doctorates from the Yugoslav era, Konstantinov is counted among Macedonia’s most influential cultural figures, leaving a lasting impact on the country’s scientific, spiritual, and cultural landscape.